Evolution and history of swimsuits

{ (up)}

IT’S HARD TO IMAGINE THAT IN THE PAST GOING TO THE BEACH DIDN’T INCLUDE THE NOW COMMON ACTIVITIES OF SWIMMING AND TANNING.

Beachwear was about protection, not just from curious eyes, but from the water and sun as well.

Apprehension towards water is rooted in the middle ages, when people thought that water could seep through the pores and cause serious damage to the body. Water, they believed, could disrupt the balance between the four humors of the human body which were responsible for a person's temper. The four humors were blood, dark and light bile and phlegm. Not only seawater was potentially dangerous, but even baths - now a routine habit - were considered a risky procedure that required certain preparations.

Starting from the 17th century people became more tolerant to the idea of washing themselves and "discovered” seawater. Initially it was used only as a therapeutic measure, however. Searching to cure a wide range of diseases from gout to infertility, doctors would recommend that patients submerse themselves in seawater for a few minutes and even drink it.

The idea of submersion meant that you shouldn’t stay in the water for more than a few minutes and contradicted the idea of swimming for pleasure. This explains why until the 20th century, when talking about seaside vacations in English the noun “bathe” was used rather than “swim”.

Sea baths in the 18th century were a complicated procedure and people would submerge fully with the help of specially trained staff. The bathers’ clothes were very different from the modern standard. Women would have sea baths in long flannel shirts which would get wet, heavy and ultimately unpleasant.

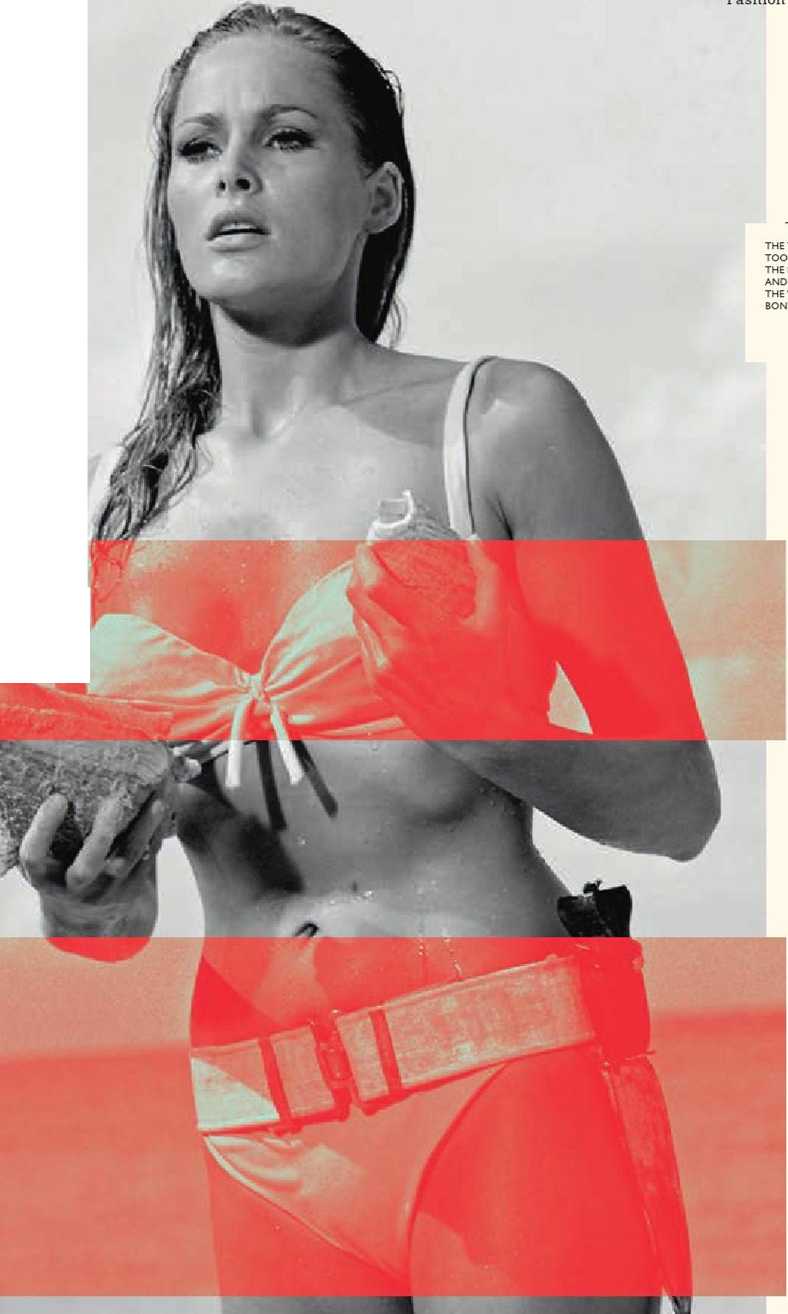

In the 19th century women’s swimsuits became slightly more open, but were meant to be worn with corsets, pantyhose, hats and even special swimming shoes. The so-called bathing cars were still in fashion, created in the mid-18th century to give swimmers some personal space. They comprised of a movable cover behind which you could change and which could then drive right into the water. The bather would bathe after entering the water and was hidden from the view of those who were on the shore.

Women couldn't relax out of the water either as the sun awaited them there. A tan was far from being considered a part of the contemporary standard of beauty - in fact, it was its greatest foe. Paleness played a big role of the ideal of women’s beauty. The tone of one's skin demonstrated social status. A tan, which currently is considered a sign of youth, wealth and beauty, was proof that you worked outdoors, in the open air. Paleness, on the other hand, was a symbol of being rich and not partaking in manual labor. This was the reason people from the “higher” classes tried to avoid getting a tan by using such things as parasols and gloves.

ON THE ROUTE TO “NEW BEAUTY”

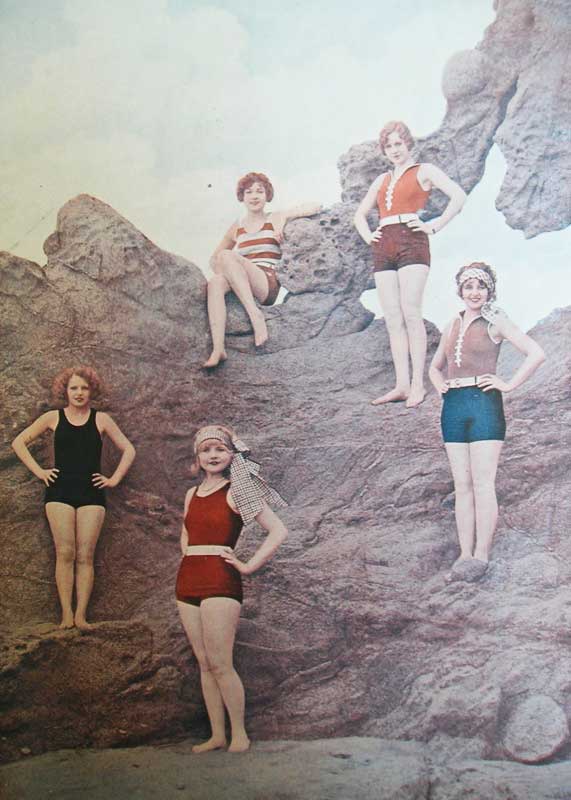

By the early 20th century industrialisation moved most lower status work indoors, into factories and plants. A shift in the perception of tans occured: now a tanned person was considered to have the time, and, hence, the money, to take sunbaths. So in the 1920s tanning came into vogue. There was a true sun rush: droves of wealthy people headed to the shores, where they gladly positioned their pale bodies under the sun. The fashion industry reacted immediately. Open swimsuits were developed, while cosmetics firms launched powders and cremes of the now fashionable bronze color and tanning oil was soon introduced.

The swimsuit changed drastically, but was still designed with a small skirt covering the buttocks and thighs, or pants that were meant to be worn with a tunic. There was a special police unit on the beaches of New York that would measure the length of the skirt and if it was shorter than what was considered decent, the offender would be asked to leave the beach immediately. No moral police, though, could stop the speedy development of swimming fashions and the new beauty standards. The heroine of the 1941 Agatha Christie novel Evil under the Sun is the personification of the new ideal: “as perfect as an ancient statue, tall, and wonderfully built, she had, from head to beautiful toe, an even bronze tan, which was accented by her simple white swimsuit with an open back".

FROM BIKINI TO BURQINI

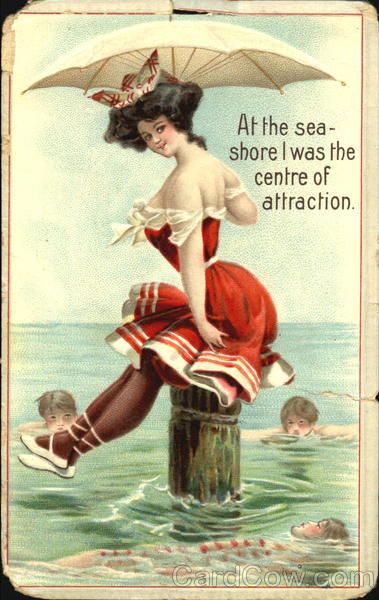

The bikini created by French designer Louis Rare in 1946 was a true explosion in the world of swimwear fashion. The 76 sq cm of cloth used in making the revolutionary swimsuit were demonstrated by the brave Michelle Bernardini, a dancer from the Parisian Casino de Paris. The bikini, named after the atoll used by the US to test nuclear weapons, had an explosive effect on its contemporaries. This swimsuit "demonstrated all but the maiden name of a woman's mother”, as an old joke goes. At first only the bravest women wore them since they could land you in a police precinct. The situation changed when the young Brigitte Bardot appeared in one in the legendary Roger Vadim film “And God created woman” in 1956.

But the true moment the bikini took center stage was when the Bond girl played by Ursula Anders came out of the sea in the white swimsuit in the first Bond film Doctor No” in 1962.

After this movie sales exploded. This, and the playful song Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini from 1960 by Amercian singer Brian Highland made the bikini a number one hit on beaches all over the world.

There’s a great variety of swimsuits for all tastes and sizes, taking into consideration religion and stylistic preference. Tankini, Bandini, thong, halter, trikini - that’s far from the full list of options of swimsuits and the variety continues to grow. A fresh player on the market is a burqini (the name comes from the words “burqa" and “bikini”), swimsuits for Muslim women. The Australian fashion designer from Lebanon Ahed Zanetti produces burqinis which cover the whole body except the face, palms and feet, yet don’t restrict movement. They are made from the light fabric used in conventional swimsuits.

The modern tendencies of the swimsuit industry are very diverse. There’s movement towards the more conservative 1980s models, on the one hand, and, on the other, the brave removal of the last extra pieces of cloth. The swimsuit fabric itself is steadily evolving, becoming lighter, faster drying and more comfortable. Sci-fi writers could have a field day taking guesses at what swimwear will look like in 100 years. Unless history, which has a habit of repeating itself, doesn’t play a cruel joke and make the sun and sea a forbidden pleasure yet again.